“You sit back in the darkness, nursing your beer, breathing in that ineffable aroma of the old-time saloon: dark wood, spilled beer, good cigars, and ancient whiskey — the sacred incense of the drinking man.”

— Bruce Aidells

“i was sitting in mcsorley’s. outside it was New York and beautifully snowing.

Inside snug and evil. the slobbering walls filthily push witless creases of screaming warmth chuck pillows are noise funnily swallows swallowing revolvingly pompous a the swallowed mottle with smooth or a but of rapidly goes gobs the and of flecks of and a chatter sobbings intersect with which distinct disks of graceful oath, upsoarings the break on ceiling-flatness

the Bar.tinking luscious jigs dint of ripe silver with warm-lyish wetflat splurging smells waltz the glush of squirting taps plus slush of foam knocked off and a faint piddle-of-drops she says I ploc spittle what the lands thaz me kid in no sir hopping sawdust you kiddo

….

and I was sitting in the din thinking drinking the ale, which never lets you grow old blinking at the low ceiling my being pleasantly was punctuated by the always retchings of a worthless lamp.”

— e.e. cummings

Excerpted from I was sitting in

mcsorley’s, 1923

Excerpted from I was sitting in

mcsorley’s, 1923

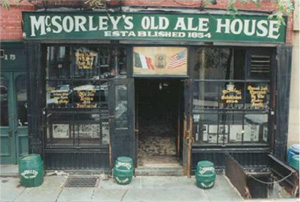

A fellow band member, who was from New York, took us one afternoon to McSorley’s Old Ale House, the oldest bar in the city. They served their own beer, which at that time was brewed in Philadelphia, by Schmidt’s. Before that, it had been made by Rheingold, in Brooklyn. Today, Pabst owns the brand. After Prohibition, the light ale was a cream stock ale. My memory is that it was pretty lightly flavored. The dark ale was a little better, but I don’t recall being particularly impressed with either.

The bar itself was dark and dusty, and usually crowded, especially on the weekends. As a result, we only went there a few times. Besides its storied past, we couldn’t see much reason to make it a regular haunt. It had only been eight years since women were even allowed in McSorley’s, and that was only because they were sued and forced to allow them. There was a place in Reading called Stanley’s that Eddie used to take me to from time to time. It was a great old dive bar, too, and at least well in to the 1980s women were not allowed at the bar, only in the dining area in back. That place was also like stepping back in time, as well. But neither had a particularly good beer selection, and that was becoming my criteria for bars.

But there was a slogan or motto at McSorley’s that always stayed with me. Be Good or Be Gone. In practice, it meant they didn’t suffer fools gladly and kicked out anybody who acted up too much or got too drunk. That was often a welcome relief as frat boys from nearby NYU weren’t allowed to get to out of hand. One advantage to being in the military in between high school and college was that it forced you to grow up a little sooner than people I knew who went straight to college. That’s not to suggest we were overly serious, but I could tell the difference whenever I visited friends at home, who had gone straight to college and who had started working. For a time, I honestly thought we should make everyone serve for one-year after high school, if not in the military then the peace corps or something like that.

By the time of my discharge in 1980, my view of beer — and also music — had been irreparably changed. I moved home to Pennsylvania and finished college, but missed the variety of beer I’d discovered in New York. I had my own place in downtown Reading when I first moved home, but Eddie threatened to kill me, hurt me, etc. whenever I saw him. He told me I couldn’t live in “his” town, so I gave him as wide a berth as possible, going out of my way to avoid him.

My mother got breast cancer and Eddie continued to make her life miserable. I stayed away as much as possible and tried to stay out of his way. The year after I got out of the Army, my mother’s cancer spread to her vital organs and she was given four months to live. Eddie couldn’t handle it and left my mother to die alone. He visited her in the hospital, drunk and carrying a meatball sandwich, when he was given the news that she was dying. When she tried to tell him she couldn’t eat a meatball sandwich after chemotherapy, he flew into a rage and threw the hero against the wall, the marinara sauce splattered on the wall like blood in horror film. That was the last we saw of Eddie until he contested the will after she died several months later. He later married another nurse, a friend of my mother’s who had pretended to be her friend in the final days, while at the same time was sleeping with Eddie.

My grandmother moved into the house where I grew up to care for her in those final months, and I moved into the attic of my Aunt’s house which was only a few blocks away. Because she had worked in a hospital most of her life, she didn’t want to die in one. All of her friends and colleagues helped her with that wish. They somehow got a hospital bed into our dining room. Her doctors and the nurses she worked with examined her and stayed with her at the house. The only reason she ever went to the hospital was for the chemo sessions. Her hair fell out in patches. She grew increasingly dramatic and depressed as her health deteriorated.

Even in those final weeks, she missed Eddie, so strong was her need to not be alone. It made me angry. Their relationship was so dysfunctional that even in leaving her to die alone, she could not find the strength to make peace with herself.

Shortly after my mother died, I married Samantha, the girl I’d been seeing for several years before that. In one of my mother’s deathbed dramas, she made Samantha promise to take care of me when she was gone. I felt obligated to marry her after that. We were married less than six months later. I was undoubtedly trying to replace the loss of my mother, but we were a poor match from the start and I should have known better. At the wedding, I had a couple of my friends keep watch at the door to make sure Eddie didn’t show up and try to ruin the day. A few days later, I moved away from Reading to a small town north of Pittsburgh. It was the first of several moves, as I bounced around managing record stores in Pennsylvania and then was promoted to buyer and moved to the company’s headquarters in North Carolina.

Once we were so far from friends and family, it became painfully obvious we were bad for one another and I finally found the courage to admit it. I was determined not to make the same mistakes my mother had, by staying in a dysfunctional marriage. We divorced shortly thereafter, less than four years after my mother’s death.

I changed jobs and started working for a local chain of video stores, and took up with a UNC student who worked at one of the stores. After I sold the house Samantha and I had bought, I moved in with the other woman. When she graduated, her next plan was law school in California. Having no particular ties to North Carolina, and not wanting to return to Pennsylvania, I seized upon her move as an opportunity to get as far away as possible. I could not be good, so I got gone.

Northern California in 1985 was at the heart of, as it was called then, the microbrewery revolution in its infancy. But as far as I could tell, it was the best place to be for a beer lover. The pressures of law school and my own demons split up yet another relationship and I found myself in California, alone and with no direction. It was a terrible time, and I was pathetic in those days, but beer yet again got me through. Eventually, both the beer and I improved. I began homebrewing. I made friends — lasting ones — and my life improved. But that’s a story for another day.

When I reflect back on all the ways beer has effected my life, both good and bad, I still marvel. People who know what I went through are often surprised not only that I still drink, but that I ever did at all. But I think they miss the point. As horrible a monster as Eddie was, even as a child I knew his behavior couldn’t be blamed on beer, or whisky, or whatever. He was a damaged person and alcohol was merely the catalyst he used to cope with his own demons. That my mother and I continually got in the way was an unfortunate consequence, but if he hadn’t been a drinker, there would have been some other trigger. He would have been a violent psychopath with or without beer. Even as a teen, I could see that I and my friends could drink beer and never become like Eddie.

It seems obvious that alcohol effects different people in different ways, but people who are against it always make that same mistake of painting the use of alcohol with one broad brush, assuming it effects everyone in similarly devastating ways. They’re wrong.

From my earliest recollections under the table to writing about beer today, beer has enriched my life, made difficult times more bearable, created life-long associations and friendships, and been a central part of my wonderful life. I used it to toast both of my children’s’ births and I gave the love of my life, my wife, a test consisting of a sampler of craft beer before I even asked her out on a date. In all of the important decisions and events of my life, beer has been there to enhance and celebrate them.

Beer was there at the dawn of civilization and it’s still part of many peoples’ lives today, as the second most enjoyed beverage after water (tea is numero uno). It has been there during good and bad times, and has been used for both. It has been considered liquid bread and the very picture of health. It has also be viewed as a scourge and a villain. It is different things to different people. Like anything that can alter one’s very spirit, it must be tolerated, even by those who shun its use. Its power is there for anyone to discover and I honestly pity those people who will not or cannot. By denying themselves, they are doing harm to their very health, both physically and spiritually.

Beer has been a part of my life as long as I can remember. It’s been both good and bad, like life itself. And that’s for one very good reason, whether you’re sitting soberly at the table or, like me, under it, having fully embraced beer. Beer is life.

No comments:

Post a Comment